byElijah Z Granet last updated 24 May 202310 minutes estimated reading time

This system is majorly indebted to the work of Sean Graham (University of Alberta), whose design of Dual Member Proportional Representation (DMP) provided an excellent system of proportional representation in the Canadian context. Principally, the context that Canada is very very big, and almost entirely empty except where it’s not. I have no doubt that his system is better suited than mine for the unique geographic and political context of Canada. I have attempted, as best I can, to design a system best fitted to the unique political and geographic context of the United Kingdom, and in doing so, have borrowed many of the brilliantly innovative elements of Graham’s DMP system.

The question of the ‘best’ electoral system is meaningless; each electoral system prioritises different values and outcomes. Furthermore, because the system changes both voting and campaigning behaviour, it is impossible to compare systems in the abstract. The complex interplay of value-judgments and outcomes was neatly summed up by UCL’s esteemed Dr Alan Renwick, who has said ‘I’ve published several books on electoral systems and every time I research electoral systems more, I get even less clear on which electoral system I think is best.’ The remarks can be heard at https://youtu.be/-r2XlSTyxsQ?t=3763. There can never be a universalist argument for a single, optimal system. Instead, the choice is about which electoral system best balances competing priorities in the specific national (or regional, etc) political and social context.

The single-member majoritarian system—often referred to as first-past-the-post, or FPTP—used for Westminster elections in the UK is, by definition, not concerned with a proportional outcome, but instead with the outcome of 650 entirely separate contests. Many, myself included, believe that the electoral system ought to be reformed to include proportional or semi-proportional representation in some form. This view is, of course, of a very longstanding one, and many, many electoral systems have been proposed for adding a proportional element to Westminster elections. These systems, ranging from the many permutations of the single-transferrable vote (STV) to the Jenkins Commission’s alternative vote plus (AV+), have one thing in common: they were not implemented.

Perhaps the most important lesson comes from the 2010 referendum on the introduction of the alternative vote (AV). AV is not a proportional system; the hope of the Liberal Democrats, who have long championed the introduction of STV, was that AV would be the first, easier step to introducing STV. The second, more difficult step would be increasing the district magnitude by merging constituencies. Yet, this first, facile step was too much change and uncertainty for the UK electorate, who resoundingly rejected the change. There were many reasons for the rejection, including the unpopularity of the spokespeople, status quo bias, and general lack of public interest, but, regardless, the result was a loud and intense rejection of a relatively minor change to the system.

My primary aim in constructing this system was to learn the lesson of this referendum—viz, that even seemingly minor changes (like introducing numbers to ballot papers) can render a voting system dead-on-arrival. Therefore, to maximise the chances of this system overcoming the considerable hurdles and opposition to reform (amongst both the electorate and institutional actors such as political parties) by, wherever possible, minimising all forms of change. The goal was to create a system which resembled FPTP to the greatest possible extent (and enjoyed its many advantages), while also introducing proportionality to the system. I sought to avoid change in every aspect of the system, from preserving parliamentary procedure (by ensuring that each member could be referred to by their constituency designation) to avoiding altering the ballot.

The result was the system enumerated below, which can achieve a largely proportional outcome while retaining as a defining feature small single-member electoral districts. The primary focus of this project was to draft an electoral system minimising, wherever possible, change to the existing system. However, it is a happy coincidence that the outcome (I hope) resembles the so-called ‘sweet spot’ identified by Carey and Hix of low-magnitude proportional representation.. Nonetheless, there are manifestly much much better better designed systems; the goal of this project is not to design a better than those already created, not least because I would clearly fail miserably at trying to outdo the brilliant minds behind existing systems. Instead, it was to create a proportional system with the highest possible chance of one day being enacted in the UK (which is still very very low).

All MPs are elected from Single Member Constituencies (SMCs). No constituency has more than one MP. Every part of the UK is simultaneously in two overlapping single member constituencies.

These are divided into two sets: the plurality constituencies and the proportional constituencies.

A proportional constituency’s is entirely coterminous with the territory of on average, 4 adjacent plurality constituencies. However, given the variance in constituency population size, some proportional constituencies will encompass more than 4 plurality constituencies and some will encompass less.

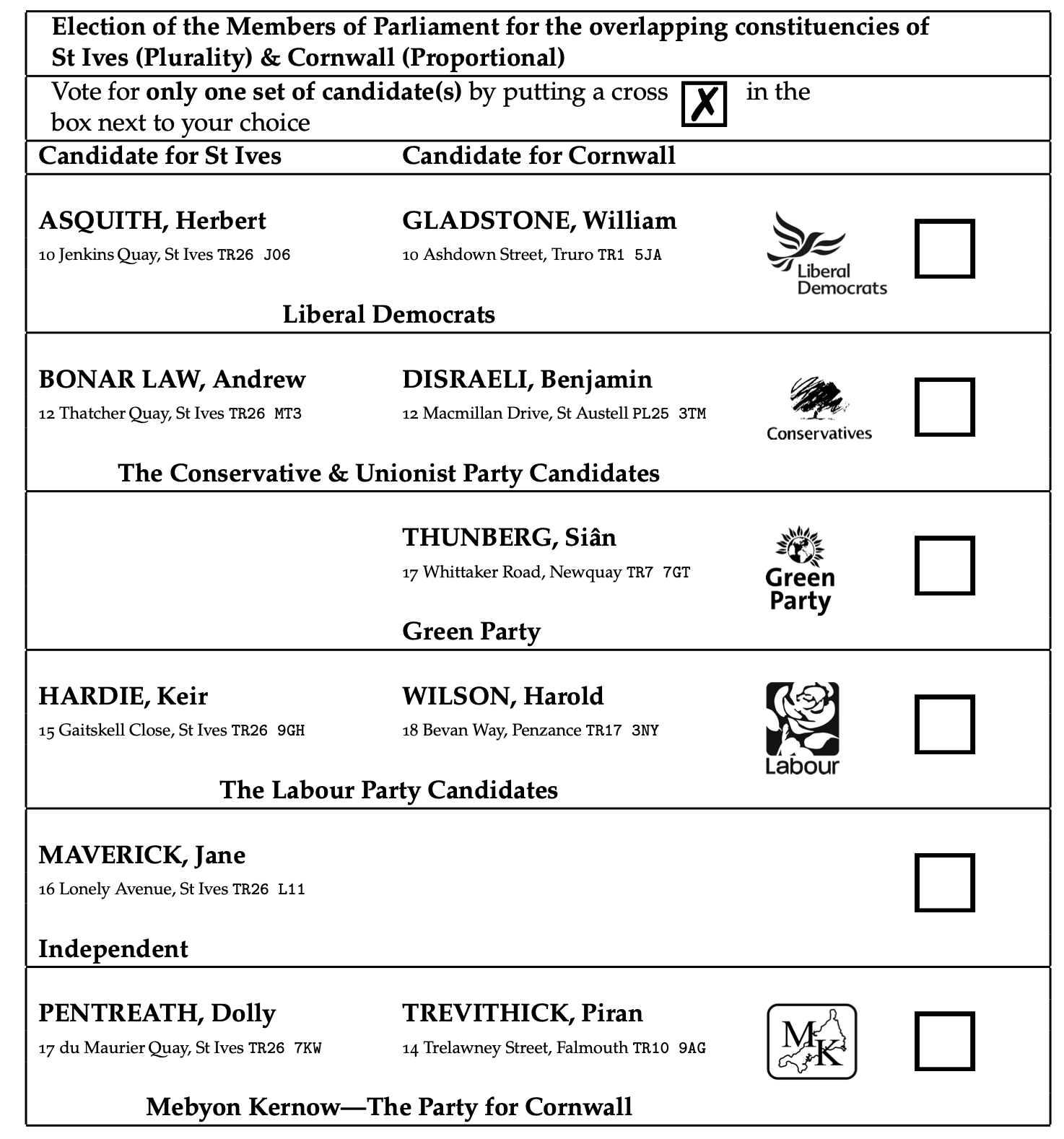

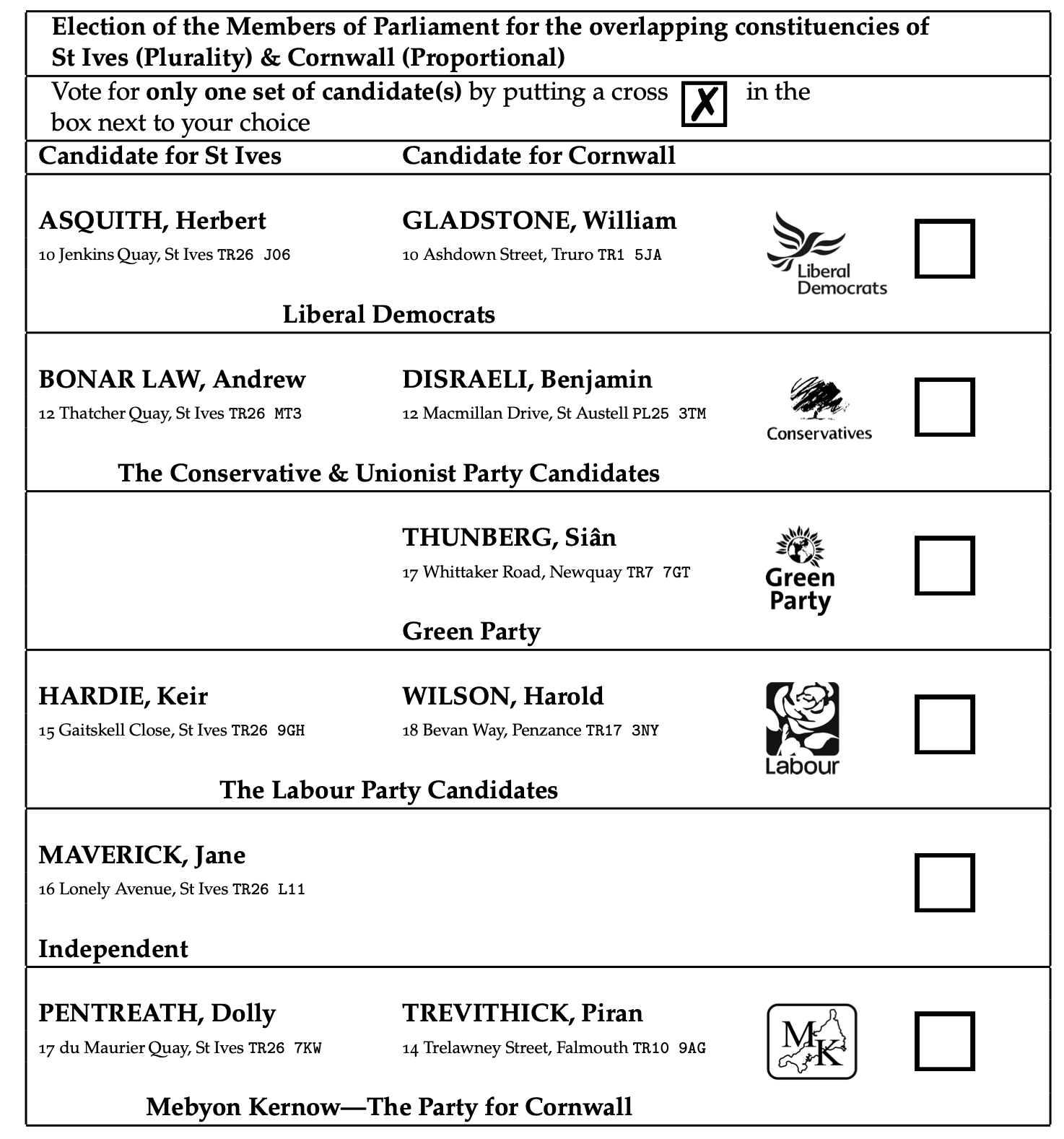

In a general election, an elector casts their vote simultaneously for their plurality and their proportional MP, by checking a box adjacent to the names of the candidate(s) for both seats. An entirely independent candidate may only run for a plurality constituency seat, although a micro-party with two candidates can stand for both a proportional and plurality seat (even if it would stand little chance of receiving enough votes to earn a proportional seat).

In each plurality constituency, the candidate with the most votes is declared the duly-elected MP for that constituency.

A party must win at least one plurality seat to be eligible for a proportional seat. Any party which fails to win a single plurality seat is thus excluded from Parliament (as is currently the case under FPTP); this functions as an electoral threshold.

The 130 proportional seats are then allocated on a national basis. The seats are awarded sequentially taking into account the seats already won (either plurality or proportional), by calculating over 130 iterative rounds the St Laguë quota of \(\frac{V}{2S+1}\), where V is total votes for the party, and S is total seats. In each round,the party with the highest quota is awarded a proportional seat.

When a party is awarded a proportional seat, the available (ie not yet elected) proportionality constituency candidate for that party with the most votes is elected as the MP for the constituency in which he or she stood.

There are no overhang or compensatory seats. Once 130 seats have been allocated, the process is completed.

There is no additional electoral deposit required for a proportional seat candidate provided the party has paid the deposit for at least one plurality seat candidate in a plurality seat located within the proportional seat.

Provided a party puts forward both at least one plurality candidate and a proportionality candidate for any overlapping set of seats, its proportionality candidate will appear on the ballot of all voters within that prpoortional seat. This means that some (but not all) voters in a given proportional seat will see just a party’s proportional candidate on their ballot. They may elect to vote for that candidate, in which case their votes will count towards the party’s total and the candidate’s internal ranking. This allows smaller parties, who for logistical or financial reasons cannot stand the full complement of candidates, to still be eligible to receive proportionality seats.

Any parties or independent candidates which do not stand against each other in any plurality or proportionality constituency may combine to form a single electoral unit for the purposes of calculating entitlements for proportionality seats. For example, the English & Welsh Greens and the Scottish Greens, which are separate parties, could combine their vote totals so as to be counted as a single party when calculating proportional entitlements. Equally, pacts between independents and parties (such as that between Dominic Grieve and the Liberal Democrats in 2019) could lead to similar arrangements, with Mr Grieve’s votes counting towards the Liberal Democrat total. This will encourage co-operation without forcing the ideologically uncomfortable party mergers required by FPTP.

Minimal change to existing system or ballot; eliminating concerns raised by AV referendum.

Retains the central link between MP and constituents

Promotes strong regional identities by empowering MPs to speak for a region at large.

Transparency: no opaque party lists. Candidates are only elected MPs of places where they appeared on the ballot (and one presumes, campaigned).

Direct link between votes for a proportionality candidate and their chances of being elected (because the vote puts them higher up the internal party list for the allocation of seats).

Avoiding multi-member districts allows the tradition of referring to members by their constituency (‘the Hon Member for South Cambridgeshire’), and prevents the need for a change to parliamentary procedure.

Avoids ‘two classes of MP’; all MPs have a specific constituency to whom they are responsible.

Avoids extremist parties being represented by retaining the current, extremely powerful threshold of having to win a plurality SMC to gain representation in Parliament. There is absolutely no possiblity of the disgraceful result produced by the party list system in the 2004 EU elections, which resulted in the BN The ‘N’ technically does not, in the most pedantic sense, literally stand for ‘Nazi’, but it basically doesP being represented in the European Parliament.

Using a national, as opposed to regional, proportional allocation of seats allows for the a high degree of proportionality with a relatively small ratio of plurality to proportionality MPs.

The St Laguë quota ensures that small parties benefit.

Yet always close link between proportional candidates and constituency

Ends the effective disenfranchisement of people in the Speaker’s constituency.

Avoids the inequality of advocates: everyone (with the minor exception of the Speaker’s constituency) has the same number of advocates in Parliament.

Allows for more equal rates of representation while retaining geographically determined constituencies: the extremes of Na h-Eileanan an Iar and the Isle of Wight can be balanced out by varying the size of proportionality seats.

Ends wasted votes by ensuring that even votes for hopeless candidates in safe seats can both boost the candidates’ party’s fortunes in the national proportional allocation and the chances of obtaining a proportional member from that list.

Allows for productive co-operation between parties.

This does nothing to resolve the very silly situation of the Speaker’s constituents being disenfranchised, although it does at least ameliorate it by giving them an actively political MP (albeit one they had no say in choosing). It is clearly preferrable that the UK adopts the system used in Ireland, where the outgoing Ceann Comhairle Think a speaker, but IRISH is auotmatically returned to the Dáil Think the first chamber of a legislature, but IRISH as an additional TD. Think an MP, but IRISH My preferred solution would to be create a bespoke Parliamentary constituency encompassing only the House of Commons chamber, whose MP is the Speaker. However, it is already difficult enough Read: virtually impossible to change the electoral system; it seemed excessive to try to fix the speakership too in one go.

Theoretically, if a party which only contests elections in one constituent part of the UK was virtually shut out of plurality seats, it could ‘run out’ of proportionality seat candidates. For example (and this is very much not the case at present), if the SNP were to get 30% of the vote in Scotland, but (due to intense competition from Labour, the Conservatives, and the Liberal Democrats) not win a single MP, This, obviously, is the sort of electoral scenario that is theoretically imaginable, but incredibly, incredibly unlikely to ever happen in reality it might be entitled to more proportionality seats than exist in Scotland. If, before an election, the SNP feared such an outcome, they might take the step of pre-emptively standing paper candidates in English plurality and proportionality seats in order to provide a buffer. This would be highly undesirable for two reasons: first, the SNP would strongly object to standing in England, and second, English voters might feel that their interests were not best represented by a proportionality MP from a party expressly uninterested in the governance of England. However, this sort of electoral scenario is extremely unlikely except as a thought experiment, because of the reality of Westminster elections. If it were to appear likely, It almost certainly won’t the obvious and amenable solution would be for Plaid Cymru and the SNP to stand as a single party for the purposes of proportionality seats (after all, the two do not stand candidates against each other and have a warm working relationship).

Theoretically, it is possible with a candidate with relatively little initial support in a local area to be elected a representative. For example, the Greens may, in the majority of constituencies in which they stand (pace Brighton Pavilion), which may lead to a relatively high number of aggregated votes but relatively few highly placed candidates. The result is a proportionality candidate for the Greens may be high up the party list with ‘only’ 10,000 votes. This is a made-up number This occurs in other systems, such as under STV (see eg Australian Senate elections), and, realistically, any proportional system results in people having at least a representative for whom not many of them voted.

The Cornwall constituency is a paradigmatic example of how SMPR’s proportional seats can be foster regional identity. By giving often neglected regions, such as Cornwall, a distinct voice in Parliament, it can help remedy regional inequalities. Additionally, the local roots of SMPR enusre the system can connect with everyday voters. Most people in Britain have lives, and therefore have never heard of the St Laguë formula, but everyone can understand the concept of an MP for Cornwall.

Three of the parties have stood candidates in both constituencies. The Green Party, however, has not stood a candidate in St Ives. This could be, for example, because of the difficulty in finding a good PPC, the lack of party organisation in the constituency, or the likelihood of losing the deposit. Obviously these are generic fictional reasons which have nothing whatsoever to do with the actual St Ives Greens, who I am sure are lovely.. However, because the Greens have stood at least one candidate in one of the other plurality constituencies in Cornwall, they are entitled to stand a candidate for the proportional seat. It then follows logically that this candidate will appear on the ballot of all voters in the constituency, regardless of which plurality seat they overlap with.

There is also an independent candidate, who is standing only in St Ives. As in FPTP, independent candidates are welcome to stand in any plurality seat. While independent candidates cannot by themselves stand in both proportional and plurality seats, because 1 < 2, groups of independents may band together to form new, small parties in their region or on the basis of a shared ideology.

The data used in the thought experiment below are largely based on the 2019 general election. However, this is emphatically not a counterfactual simulation, nor even a rough guess of what the results of the 2019 election would have been under SMPR. As noted before (but it bears strenuous repeating), the system is not a neutral variable that can be changed while leaving everything else the same. There is no ceteris paribus with electoral systems, because the system shapes the entire election. UK voters are incredibly accustomed to the FPTP system, and voting choices under the system are shaped by it.. That’s before even considering how alterations to electoral law and constituency boundaries might shape inter- or intra-party competition; furthermore, the changed electoral realities of a different system might have dissuaded various parties from even supporting an election in 2019 in the first place.

The maths below are just a way to see the output SMPR would produce on a relatively plausible input. They have no predictive value. They have no counterfactual value. Instead, their value is in demonstrating how the proportional features of SMPR intervene to alter parliamentary composition following (an entirely fictional, but not unrealistic) single-member constituency result. In that sense, this section is useful; it ought not to be mis-used.

There are 520 plurality seats, which we can assume have been carefully and correctly apportioned by the four Boundary Commissions. Although it is unclear how voter behaviour might be altered by the knowledge that votes for poorly placed local candidates are no longer ‘wasted’, let us imagine Read: I cannot be bothered to make up new numbers a world where the results broadly resemble 2019’s. Using the 2019 election data, and mmp-calc Available at this link., I proportionally distributed (using the St Laguë quota) the seats won at the 2019 election (650 plurality seats) into a 520 plurality seat Parliament, making for arbitrary reasons and without any evidence the wildly inaccurate assumption that the plurality seat distribution would be proportionally the same under SMPR. I really want to emphasise that this assumption is just for illlustration, and absolutely not how a real election would have gone.. For simplicity’s sake, I assigned the Speaker’s seat to Labour when tallying up the 650 distributions, as it was a Labour safe seat. Also this is already such an arbitrary exercise that one more arbitrary choice can’t hurt.. The results are shown in Table 1.

| Current | SMPR | |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 650 | 520 |

| CON | 365 | 292 |

| LAB | 203 | 162 |

| SNP | 48 | 38 |

| LD | 11 | 9 |

| DUP | 8 | 6 |

| SF | 7 | 6 |

| PC | 4 | 3 |

| SDLP | 2 | 2 |

| GRN | 1 | 1 |

| APNI | 1 | 1 |

Now, once again using the St Laguë quota and mmp-calc.py, as well as the voting data for 2019 cited above, Like , I used the figure for votes for all Green parties as the Green total. I distributed the 130 proportional seats to the 10 parties. The results can be seen in Table 2:

| Party | Plur'ySeats | Propor’lSeats | Total | Diff.from2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | 292 | 0 | 292 | −73 |

| LAB | 162 | 46 | 208 | +5 |

| SNP | 38 | 0 | 38 | −10 |

| LD | 9 | 66 | 75 | +64 |

| DUP | 6 | 0 | 6 | −2 |

| SF | 6 | 0 | 6 | −1 |

| PC | 3 | 0 | 3 | −1 |

| SDLP | 2 | 0 | 2 | +0 |

| GRN | 1 | 16 | 17 | +16 |

| APNI | 1 | 2 | 3 | +2 |

At the outset, I established the criterion by which this system was to primarily be judged: can it maximise its proportionality while minimising change to FPTP, and thus increase the chance of eventual adoption?

The minimal change involved in SMPR shows it meets the first criterion perhaps as well as any system which is not literally FPTP could. There are no pesky numbers or panachage ballots here. The task now, therefore, is to see how proportional this entirely imaginary and unrealistic outcome is.

The standard way Sorry, Loosemore-Hanby. of measuring disproportionality is through the least-squares index developed by Gallagher. As its name implies, the index is calculated using the formula below:

$$I=\frac{\textstyle\sum^{n}_{i=1} (s_i -v_i)^2 }{2}$$ $$\begin{aligned} \textrm{Where}&&\\ s&=&\textrm{The number of seats for a given party}\\ v &=&\textrm{The number of votes for a given party}\\ \end{aligned}$$

The table below indicates that SMPR is noticeably more proportional in these measures, with most parties gaining reasonable approximations of their vote share. I repeat the strenuous, emphatic Health Warning given above: this is not what a ‘typical’ election under SMPR would give, and it is not a model of future or past elections. It is simply a good indicator that SMPR can produce quite proportional outcomes (in this case, ones which are equal or better to many countries with proportional representation).

| Party | FPTP % of Seats | % of Votes | SMPR % of Seats |

|---|---|---|---|

| CON | 56.15 | 43.63 | 44.92 |

| LAB | 31.23 | 32.08 | 32.00 |

| SNP | 7.38 | 3.88 | 5.85 |

| LD | 1.69 | 11.55 | 11.54 |

| DUP | 1.23 | 0.76 | 0.92 |

| SF | 1.08 | 0.57 | 0.92 |

| PC | 0.62 | 0.48 | 0.46 |

| SDLP | 0.31 | 0.37 | 0.31 |

| GRN | 0.15 | 2.70 | 2.62 |

| APNI | 0.15 | 0.42 | 0.46 |

| Gall. Index | ~ 12.5 | ~ 4 |

© , Elijah Granet, but licensed to all under the terms of Creative Commons licence CC-BY-SA 4.0